Chapter 6 Judgmental forecasts

There are three general settings in which judgmental forecasting is used:

- there are no available data so that statistical methods are not applicable and judgmental forecasting is the only feasible approach

- data are available, statistical forecasts are generated, and these are then adjusted using judgement

- data are available and statistical and judgmental forecasts are generated independently and then combined

It is important to recognise that judgmental forecasting is subjective and comes with limitations. However, implementing systematic and well-structured approaches can confine these limitations and markedly improve forecast accuracy.

Whenever data are available, applying statistical methods (such as those discussed in other chapters of this book), is preferable and should always be used as a starting point.

6.1 Beware of limitations

Judgmental forecasts are subjective, and therefore do not come free of bias or limitations.

Judgmental forecasts can be inconsistent. Unlike statistical forecasts, which can be generated by the same mathematical formulas every time, judgmental forecasts depend heavily on human cognition, and are vulnerable to its limitations.

Judgement can be clouded by personal or political agendas, where targets and forecasts (as defined in Chapter 1) are not segregated.

Another undesirable property which is commonly seen in judgmental forecasting is the effect of anchoring. In this case, the subsequent forecasts tend to converge or be close to an initial familiar reference point

6.2 Key principles

Set the forecasting task clearly and concisely

All definitions should be clear and comprehensive, avoiding ambiguous and vague expressions. Also, it is important to avoid incorporating emotive terms and irrelevant information that may distract the forecaster.

Implement a systematic approach

Forecast accuracy and consistency can be improved by using a systematic approach to judgmental forecasting involving checklists of categories of information which are relevant to the forecasting task.

Document and justify

Formalising and documenting the decision rules and assumptions implemented in the systematic approach can promote consistency, as the same rules can be implemented repeatedly.

Systematically evaluate forecasts

Keep records of forecasts and use them to obtain feedback when the corresponding observations become available.

Segregate forecasters and users

Forecasters and users should be clearly segregated. A classic case is that of a new product being launched. The forecast should be a reasonable estimate of the sales volume of a new product, which may differ considerably from what management expects or hopes the sales will be in order to meet company financial objectives. In this case, a forecaster may be delivering a reality check to the user.

The way in which forecasts may then be used and implemented will clearly depend on managerial decision making. For example, management may decide to adjust a forecast upwards (be over-optimistic), as the forecast may be used to guide purchasing and stock keeping levels. Such a decision may be taken after a cost-benefit analysis reveals that the cost of holding excess stock is much lower than that of lost sales. This type of adjustment should be part of setting goals or planning supply, rather than part of the forecasting process.

6.3 The Delphi method

The Delphi method was invented by Olaf Helmer and Norman Dalkey of the Rand Corporation in the 1950s for the purpose of addressing a specific military problem. The method relies on the key assumption that forecasts from a group are generally more accurate than those from individuals. The aim of the Delphi method is to construct consensus forecasts from a group of experts in a structured iterative manner. A facilitator is appointed in order to implement and manage the process. The Delphi method generally involves the following stages:

Assemble a panel of experts in various fields concerned

Forecasting tasks/challenges are set and distributed to the experts.

Experts return initial forecasts and justifications. These are compiled and summarised in order to provide feedback.

Feedback is provided to the experts, who now review their forecasts in light of the feedback. This step may be iterated until a satisfactory level of consensus is reached.

Final forecasts are constructed by aggregating the experts’ forecasts.

6.3.1 Experts and anonymity

The first challenge of the facilitator is to identify a group of experts who can contribute to the forecasting task. The usual suggestion is somewhere between 5 and 20 experts with diverse expertise(maily decided by the facilitator). Experts submit forecasts and also provide detailed qualitative justifications for these.

A key feature of the Delphi method is that the participating experts remain anonymous at all times. This means that the experts cannot be influenced by political and social pressures in their forecasts.Anonymity of the experts may be an advantage in not suppressing creativity, but could hinder collaboration.

Anonymity also means Delphi method is not constrained by physical location, rendering it economical.

6.3.2 Setting the forecasting task in a Delphi

It may be useful to conduct a preliminary round of information gathering from the experts before setting the forecasting tasks. Alternatively, as experts submit their initial forecasts and justifications, valuable information which is not shared between all experts can be identified by the facilitator when compiling the feedback.

6.3.3 Iteration

The process of the experts submitting forecasts, receiving feedback, and reviewing their forecasts in light of the feedback, is repeated until a satisfactory level of consensus between the experts is reached. Satisfactory consensus does not mean complete convergence in the forecast value; it simply means that the variability of the responses has decreased to a satisfactory level. Usually two or three rounds are sufficient. Experts are more likely to drop out as the number of iterations increases, so too many rounds should be avoided.

6.3.4 Final forecasts

The final forecasts are usually constructed by giving equal weight to all of the experts’ forecasts. However, the facilitator should keep in mind the possibility of extreme values which can distort the final forecast.

6.3.5 Limitations and variations

Due to the iteration process, Delphi method can be time-consuming compared to a group meeting. Anonymity of the experts may be an advantage in not suppressing creativity, but could hinder collaboration.

Also, In a group setting, personal interactions can lead to quicker and better clarifications of qualitative justifications. A variation of the Delphi method which is often applied is the “estimate-talk-estimate” method, where the experts can interact between iterations, although the forecast submissions can still remain anonymous. A disadvantage of this variation is the possibility of the loudest person exerting undue influence.

6.3.6 The facilitator

The facilitator is largely responsible for the design and administration of the Delphi process. The facilitator is also responsible for providing feedback to the experts and generating the final forecasts. In this role, the facilitator needs to be experienced enough to recognise areas that may need more attention, and to direct the experts’ attention to these. Also, as there is no face-to-face interaction between the experts, the facilitator is responsible for disseminating important information.

6.4 Forecasting by analogy

A useful judgmental approach which is often implemented in practice is forecasting by analogy. A common example is the pricing of a house through an appraisal process. An appraiser estimates the market value of a house by comparing it to similar properties that have sold in the area. The degree of similarity depends on the attributes considered. With house appraisals, attributes such as land size, dwelling size, numbers of bedrooms and bathrooms, and garage space are usually considered.

Alternatively, a structured approach comprising a panel of experts can be implemented. The concept is similar to that of a Delphi; however, the forecasting task is completed by considering analogies . First, a facilitator is appointed. Then the structured approach involves the following steps.

A panel of experts who are likely to have experience with analogous situations is assembled.

Tasks/challenges are set and distributed to the experts.

Experts identify and describe as many analogies as they can, and generate forecasts based on each analogy.

Experts list similarities and differences of each analogy to the target situation, then rate the similarity of each analogy to the target situation on a scale.

Forecasts are derived by the facilitator using a set rule. This can be a weighted average, where the weights can be guided by the ranking scores of each analogy by the experts.

Because of the similarity of fundamental principle and procedure, the analogy method share what the Delphi method benifits and suffers.

6.5 Scenario forecasting

A fundamentally different approach to judgmental forecasting is scenario-based forecasting. The aim of this approach is to generate forecasts based on plausible scenarios. In contrast to the two previous approaches (Delphi and forecasting by analogy) where the resulting forecast is intended to be one likely outcome, scenario foreasting is about making multiple parallel futures (i.e., scenarios), each of which may have a low possibility to occur. The scenarios are generated by considering all possible factors or drivers, their relative impacts, the interactions between them, and the targets to be forecast.

Building forecasts based on scenarios allows a wide range of possible forecasts to be generated and some extremes to be identified. For example it is usual for “best”, “middle” and “worst” case scenarios to be presented, although many other scenarios will be generated. Thinking about and documenting these contrasting extremes can lead to early contingency planning.

With scenario forecasting, decision makers often participate in the generation of scenarios. While this may lead to some biases, it can ease the communication of the scenario-based forecasts, and lead to a better understanding of the results.

6.6 New product forecasting

A common use of judemental forecasting is to predict sales of a new product. It may be an entirely new product which has been launched, a variation of an existing product (“new and improved”), a change in the pricing scheme of an existing product, or even an existing product entering a new market.

The approaches we have already outlined (Delphi, forecasting by analogy and scenario forecasting) are all applicable when forecasting the demand for a new product.

Other methods which are more specific to the situation are also available. We briefly describe three such methods which are commonly applied in practice. These methods are less structured than those already discussed, and are likely to lead to more biased forecasts as a result.

Whichever method of new product forecasting is used, it is important to thoroughly document the forecasts made, and the reasoning behind them, in order to be able to evaluate them when data become available.

6.6.1 Sales force composite

In this approach, forecasts for each outlet/branch/store of a company are generated by salespeople, and are then aggregated. This usually involves sales managers forecasting the demand for the outlet they manage. Salespeople are usually closest to the interaction between customers and products, and often develop an intuition about customer purchasing intentions. They bring this valuable experience and expertise to the forecast.

However, having salespeople generate forecasts violates the key principle of segregating forecasters and users, which can create biases in many directions.

6.6.2 Executive opinion

In contrast to the sales force composite, this approach involves staff at the top of the managerial structure generating aggregate forecasts. Such forecasts are usually generated in a group meeting, where executives contribute information from their own area of the company. Having executives from different functional areas of the company promotes great skill and knowledge diversity in the group.

This process carries all of the advantages and disadvantages of a group meeting setting which we discussed earlier. In this setting, it is important to justify and document the forecasting process. That is, executives need to be held accountable in order to reduce the biases generated by the group meeting setting. There may also be scope to apply variations to a Delphi approach in this setting; for example, the estimate-talk-estimate process described earlier.

6.6.3 Customer intentions

Customer intentions can be used to forecast the demand for a new product or for a variation on an existing product. Questionnaires are filled in by customers on their intentions to buy the product. A structured questionnaire is used, asking customers to rate the likelihood of them purchasing the product on a scale; for example, highly likely, likely, possible, unlikely, highly unlikely.

Survey design challenges, such as collecting a representative sample, applying a time- and cost-effective method, and dealing with non-responses, need to be addressed.9

Furthermore, in this survey setting we must keep in mind the relationship between purchase intention and purchase behaviour. Customers do not always do what they say they will. Many studies have found a positive correlation between purchase intentions and purchase behaviour; however, the strength of these correlations varies substantially. The factors driving this variation include the timings of data collection and product launch, the definition of “new” for the product, and the type of industry. Also, the correlation between intention and behaviour is found to be stronger for variations on existing and familiar products than for completely new products.

6.7 Judgmental adjustments

In this final section, we consider the situation where historical data are available and are used to generate statistical forecasts. And then practitioners attempt to apply judgmental adjustments to these forecasts.

Judgemental forecasts provide an avenue for incorporating factors that may not be accounted for in the statistical model, such as promotions, large sporting events, holidays, or recent events that are not yet reflected in the data. However, these advantages come to fruition only when the right conditions are present. Judgmental adjustments, like judgmental forecasts, come with biases and limitations, and we must implement methodical strategies in order to minimise them.

6.7.1 Use adjustments sparingly

Judgmental adjustments should not aim to correct for a systematic pattern in the data that is thought to have been missed by the statistical model. This has been proven to be ineffective, as forecasters tend to read non-existent patterns in noisy series. Statistical models are much better at taking account of data patterns, and judgmental adjustments only hinder accuracy.

Judgmental adjustments are most effective when there is significant additional information at hand or strong evidence of the need for an adjustment. We should only adjust when we have important extra information which is not incorporated in the statistical model. Hence, adjustments seem to be most accurate when they are large in size. Small adjustments (especially in the positive direction promoting the illusion of optimism) have been found to hinder accuracy, and should be avoided.

6.7.2 Apply a structured approach

Using a structured and systematic approach will improve the accuracy of judgmental adjustments. Following the key principles outlined in Section 6.2 is vital. In particular, having to document and justify adjustments will make it more challenging to override the statistical forecasts, and will guard against unnecessary adjustments.

It is common for adjustments to be implemented by a panel (see the example that follows). Using a Delphi setting carries great advantages.

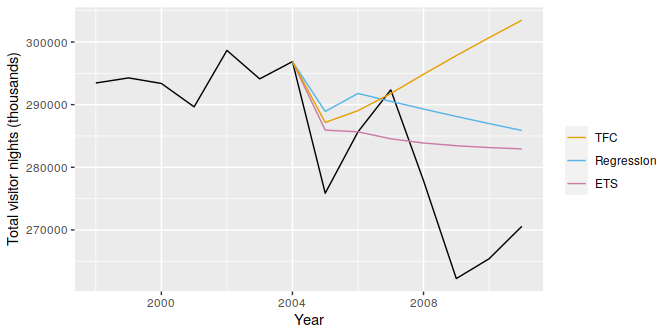

6.7.3 Example: Tourism Forecasting Committee (TFC)

Tourism Australia publishes forecasts for all aspects of Australian tourism twice a year. The published forecasts are generated by the TFC, an independent body which comprises experts from various government and industry sectors; for example, the Australian Commonwealth Treasury, airline companies, consulting firms, banking sector companies, and tourism bodies.

The forecasting methodology applied is an iterative process. First, model-based statistical forecasts are generated by the forecasting unit within Tourism Australia, then judgmental adjustments are made to these in two rounds. In the first round, the TFC Technical Committee (comprising senior researchers, economists and independent advisers) adjusts the model-based forecasts. In the second and final round, the TFC (comprising industry and government experts) makes final adjustments. In both rounds, adjustments are made by consensus.

Figure 6.1: Long run annual forecasts for domestic visitor nights for Australia, comparing regression models, ETS(Exponetial Smoothing) and judgmental adjustsments by TFC.

What can we learn from this example? Although the TFC clearly states in its methodology that it produces ‘forecasts’ rather than ‘targets’, could this be a case where these have been confused? Are the forecasters and users sufficiently well-segregated in this process? Could the iterative process itself be improved? Could the adjustment process in the meetings be improved? Could it be that the group meetings have promoted optimism ?